An introduction to contract testing - part 2 - introducing contract testing

This post was published on May 26, 2021In this series of articles, you’ll be introduced to a (fictitious but realistic) use case for consumer-driven contract testing with Pact and Pactflow. Over 6 articles, you’ll read about:

- The different parties that play a role in this use case and the challenges that integration and end-to-end testing pose for them

- How contract testing can address these challenges (this article)

- How to use Pact for consumer-driven contract testing

- How to make contract testing an integral part of an automated development and delivery workflow

- What the effect is of changes in the expectations and implementations of the consumer and provider parties

- How to invite new parties to the contract testing ecosystem and how bidirectional contracts can make this a smooth process

All code samples that are shown and referenced in these articles can be found on GitHub.

In the previous article, we’ve been introduced to a fictitious online sandwich store and a number of its loosely coupled components. We’ve also seen that because these components are being developed in different teams, integration and end-to-end testing comes with a number of challenges. In this article, you’ll learn what contract testing is, what consumer-driven contract testing looks like and how it addresses the challenges faced by our online sandwich store.

What makes integration testing so difficult?

The previous article contained a number of reasons for integration testing being so difficult in our case, being:

- To perform end-to-end tests, a complex test environment consisting of all components involved needs to be provisioned every time these tests need to be run

- Different components being developed in different teams, each with their own delivery heartbeat and feature backlog, means that teams often have to wait for other teams to finish their work before integration testing can be performed

- It is not always clear who is responsible for the integration testing, since the scope of these tests crosses individual team boundaries

- Since the Address team is located on the other side of the country, there’s a communication barrier as it is not possible to simply walk over to their desk. A lot of communication is done via email, Slack and Jira, but a lot of information goes lost in translation

The root cause behind most of the problems above is that integration testing is perceived to be a synchronous activity. To perform integration testing, the different components required for a particular test should be (made) available at the same moment in time, typically just before the test is run.

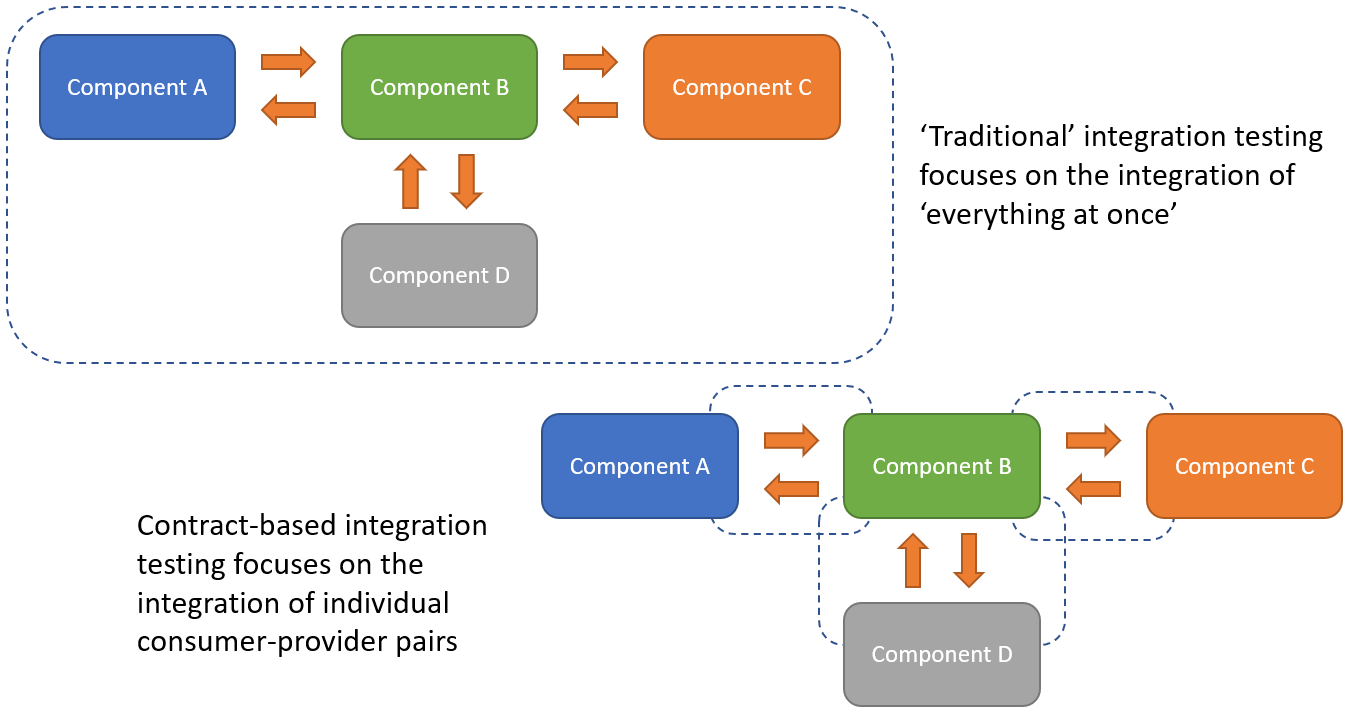

The larger the scope of the integration test, the more components typically will be involved, and the more challenging the setting up of a suitable test environment will be. While our case is intentionally kept small, in a real-world situation we might be looking at dozens or sometimes even hundreds of components that together form an application to be tested, and all of these components should be (made) available every time a test needs to be run. No wonder that many teams and organizations have a hard time creating and maintaining a reasonable amount of integration and end-to-end testing coverage!

Introducing contract testing

Enter contract testing. The aim of contract testing is to transform integration testing from a synchronous to an asynchronous activity. Instead of spinning up large parts of and sometimes even the entire application at once before running the tests, contract testing zooms in on individual pairs of components: a consumer and a provider.

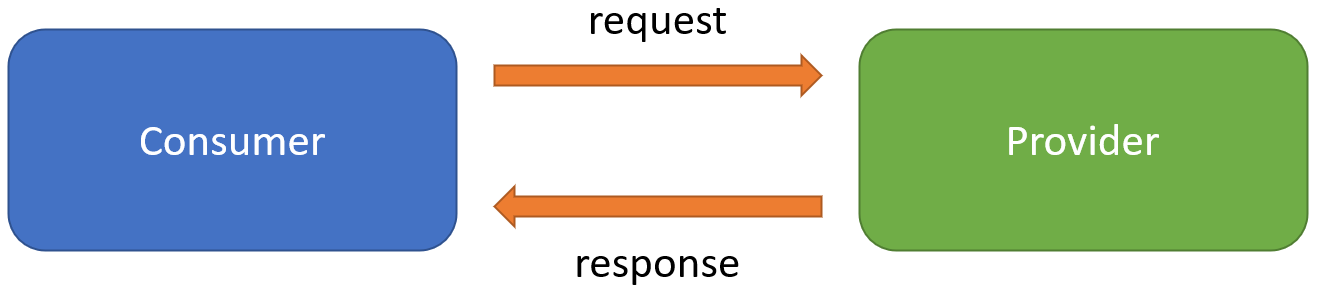

In any distributed system, components work together by exchanging data. A consumer requests data from a provider (or sends data to a provider, or updates or deletes existing data…), and the provider responds either with the requested data (or a confirmation message) or with a suitable response indicating that something went wrong.

Contract testing looks at each individual connected pair of components and verifies whether each of these pairs is able to communicate according to the specifications (or expectations) at any given point in time. If all consumer-provider pairs are able to communicate with one another, there should not be any issues at the integration level.

Note that contract testing in this sense does not replace functional testing of individual components. It specifically targets integration issues that occur when different components exchange data, but it does not verify the implementation of any single component. The latter is part of the functional testing responsibilities of the individual teams tasked with the development of each component.

For a more detailed description of the concept of contract testing, please have a look at this article.

How does contract testing work?

Contract testing, as the name suggests, uses contracts to formalize the expectations that any pair of consumer and provider have with regards to how ‘the other half’ behaves. There are essentially two flavours of contract testing, and their main difference is who’s responsible for creating the contract:

- In consumer-driven contract testing, it’s the consumer who creates the contract. This contract contains the expectations that a consumer has about the way in which the provider responds to specific types of requests. It’s the provider’s job to prove that they can meet the expectations formalized in the contract

- In provider-driven contract testing, it’s the provider who creates the contract. This contract is more of a specification in the ‘this is what I do’ style. Consumers can use these provider-generated contracts to ensure that they can process the different types of responses listed in there successfully.

There are pros and cons to both flavours of contract testing, some of which are described here. In the remainder of this article and the following articles, we’ll be looking at consumer-driven contract testing (or CDCT) only. This is also the flavour of contract testing that is used most often in practice, and the tools that we’ll see are written to support CDCT as well.

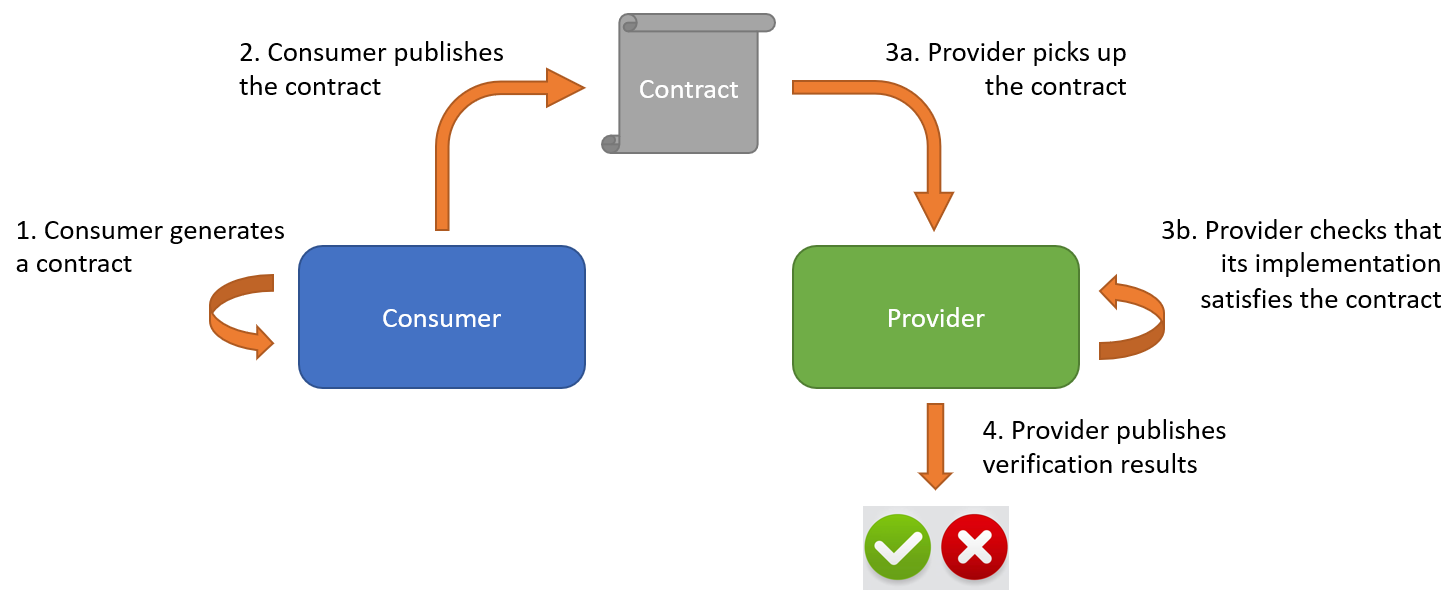

A complete CDCT cycle covering the verification that a given consumer-provider pair can communicate with one another consists of four steps:

- The consumer generates a contract containing their expectations about the behaviour of a provider

- The consumer publishes the contract for the provider to pick up

- The provider picks up the contract and checks that its current implementation meets the expectations expressed by the consumer in the contract

- The provider publishes the verification results to inform the consumer

This process is what makes CDCT (and contract testing in general) an asynchronous method of integration testing: the consumer and provider perform the steps they’re responsible for as part of their own build process, without having to rely on their connected components to be available at that time. All expectations that consumers have of their providers are written down in a contract, and each party performs their integration testing due diligence as part of their own build and release process.

As an example, let’s walk through the aforementioned steps in a little more detail using an example from our sandwich store. For this example, we’ll focus on the Customer API as a consumer and the Address API as a provider. Please refer to the previous article in this series for a more detailed explanation of what these components do. More specifically, we’ll consider the GET operation that is exposed by the Address API and that is invoked by the Customer API to get details of a specific address associated with a customer:

GET /address/{id}

For now, let’s also assume we’re only interested in the HTTP response codes that this GET operation returns. In the next article, we’ll take a closer look at the other expectations that the Customer API might have about the response from the Address API, mainly the actual data that will be returned by the latter.

Regarding the HTTP status codes, the Customer API might have the following expectations:

- “When I request data using an

{id}that is present in the database, I expect the response code to be HTTP 200.” - “When I request data using an

{id}that is correctly formatted, but not present in the database, I expect the response code to be HTTP 404.” - “When I request data using an

{id}that is incorrectly formatted, I expect the response code to be HTTP 400.”

In the first step of the CDCT process, the Customer API creates a contract that contains these expectations in a standardized format. The Customer API then publishes this contract to a central place where the provider, in this case the Address API, can pick up it for verification. In the third step, the provider verifies that its current implementation meets all the expectations that are formalized in the contract, and finally, it communicates the verification results to a central place again, so the consumer knows that:

- the provider is able to meet all expectations and all is well, or

- the provider is unable to meet all expectations, and a conversation should be started to resolve the integration issue(s)

As you can see from this example, a contract is an agreement between a single consumer (the Customer API here), and a single provider (the Address API here). This means that when a provider component is consumed by X different consumers, and all of these consumers have implemented CDCT, the provider has to satisfy the expectations in X(*) different contracts to ensure that there are no integration issues. It goes without saying that the larger the amount of consumers, the higher the risk of potential conflicts of interest. We’ll see a detailed example of this in a later article.

(*) In our sandwich shop example, X is equal to 2, as the Address API is consumed by both the Customer API and the Order API.

In this article, you’ve seen what the aims of contract testing are and how it aims to make integration testing an asynchronous activity rather than a synchronous one. If you’re still unclear whether contract testing is for you, this article gives a good overview of the pros and cons of contract testing for different contexts.

In the next article, we’ll (finally!) dive into some code and see how we can implement the CDCT steps outlined in this article using Pact.

"