Breaking down your E2E tests - an example

This post was published on February 8, 2024Over the last year or two, I’ve found myself talking about contract testing more and more often, in talks, workshops, as well as when I’m working with clients. One of the promises of contract testing is that it will help reduce your dependency on long, slow, expensive end-to-end tests. But how does that work in practice?

And more generally speaking, how can teams stop relying so much on slow and expensive E2E testing in general?

Note: I’m not saying you should remove all E2E tests by breaking them down into smaller pieces, but for a lot of tests, this might be a very useful thought exercise. Thank you to Justas Laužadis for the discussion on this.

In this blog post, I want to have a look at an example E2E test for ParaBank, a fictional online bank, and break that test down step by step into smaller, more focused tests. The test focuses on applying for a loan through the ParaBank website and checking that, given certain input values, the response returned on screen matches expectations.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume the architecture for this feature consists of three separate components:

- The graphical user interface, responsible for enabling a user to submit a loan application and view the result on screen

- The ParaBank business logic layer, responsible for gathering the user input, augmenting it with information about the currently logged-in user and sending a loan application request to the loan processor, and

- The loan processor, responsible for determining whether the loan application can be approved

The first two components are internal to ParaBank, the loan processor is a public, third-party service consumed by ParaBank, as well as by many other online banking systems.

Let’s also assume that all components already write and use (unit or component) tests for fast feedback on changes to their respective behaviour.

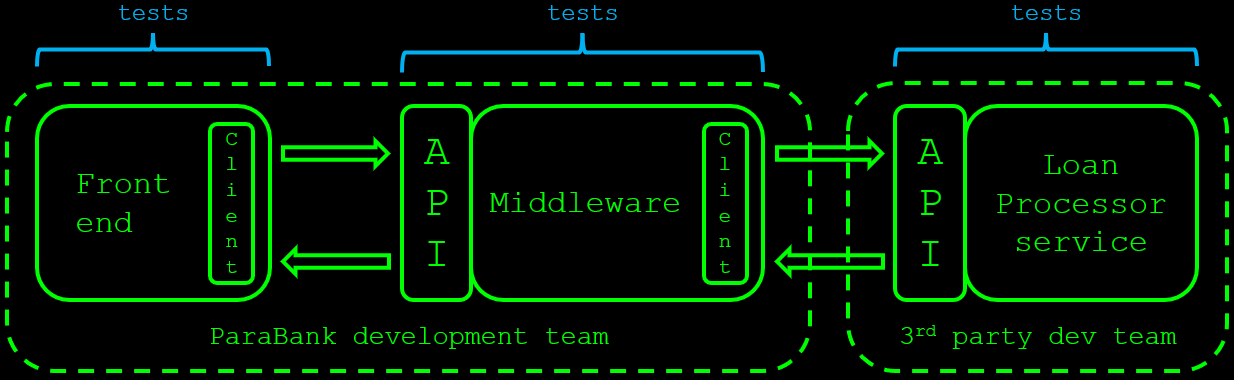

Here’s what that looks like:

Step 0: Writing E2E tests

In situations like this, I used to resort to writing a couple of E2E tests that simulate a ParaBank user logging in to the system, filling in the loan application form and submitting it using various different input values, and verifying the corresponding result on screen.

I still see many teams do the exact same thing, either because they don’t know any better, or because there is some kind of belief that ‘if we don’t see it work in the UI, we don’t believe or trust our tests’.

Such a test, written with a tool like Selenium or Playwright, might look something like this:

[TestCase(10000, 1000, 12345, "Approved")]

[TestCase(10000, 100, 12345, "Denied")]

[TestCase(50000, 1000, 12345, "Denied")]

public void ApplyForLoan_CheckResult_ShouldEqualExpectations

(int loanAmount, int downPayment, int fromAccount, string expectedResult)

{

new LoginPage(this.driver)

.LoginAs("john", "demo");

new AccountOverviewPage(this.driver)

.SelectMenuItem("Request Loan");

var rlp = new RequestLoanPage(this.driver);

rlp.SubmitLoanRequest(loanAmount, downPayment, fromAccount);

Assert.That(rlp.GetLoanApplicationResult(), Is.EqualTo(expectedResult));

}and the scope of this test can be visualized like this:

While having tests like this might seem like a good idea, there are several problems with E2E tests that you will face at some point:

- Writing these tests takes a long time - E2E test code is actually the hardest form of automation there is, which is why I still think it is weird that so many people start their automation learning journey with tools like Selenium or Playwright

- Executing these tests takes a long time - Starting and stopping browsers, loading websites, communicating with third party systems, it all adds up

- Pinpointing failures in these tests takes a long time - Because there are so many moving parts, it is often hard to find the root cause of a test failure, and this root cause is more likely to be found in the test itself rather than in the application code that is tested

Also, writing and running these E2E tests typically only happens at very late stages in the development cycle, since it requires all components and services to be available for testing, which goes against the wish of many teams to get fast feedback on their development efforts.

So, let’s start improving this test step by step by breaking it down into smaller pieces that are easier to write and quicker to run.

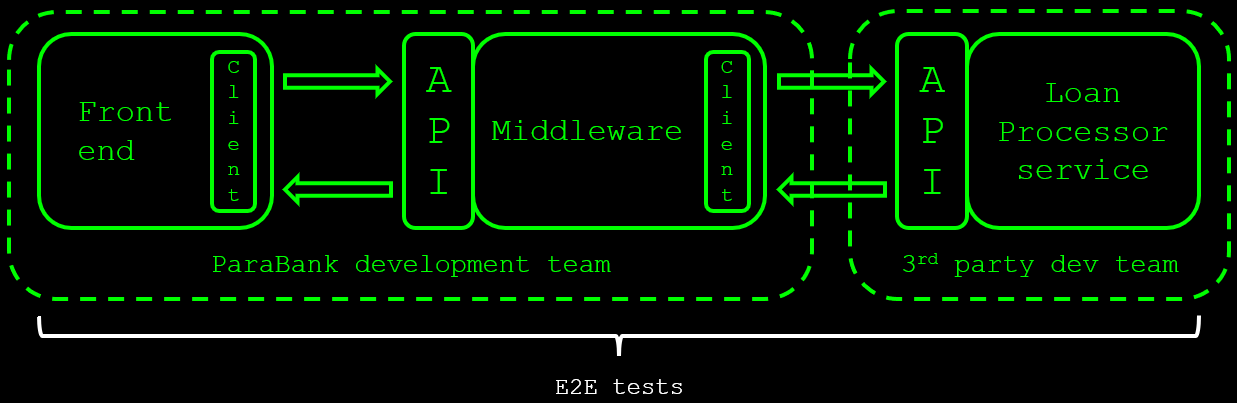

Step 1: Separating the frontend tests from the rest

In their current state, our E2E tests are verifying multiple things all at the same time. This is generally a bad idea, as it makes it harder to pinpoint the root cause of an issue in case of test failures. Let’s start breaking down our test by making a distinction between

‘Can a user see the loan application result in their browser?’

and

‘Is the submitted loan application processed correctly and does the loan application result match our expectations?’

When we make this distinction, the scope of our tests now looks like this:

We have unit / component tests for our frontend, with calls to the API mocked by your testing library of choice, and the API calls that now drive our tests for the backend can be written using tools like Postman or libraries like RestAssured.Net.

This is a definite improvement over our original E2E tests, but there are still some problems left to be solved:

- Our API-driven backend test still involves several layers and components

- Compared to our previous E2E test, we’ve lost the testing of the integration between our frontend (now tested in isolation) and the ParaBank backend

This means we’ve got some more work to do!

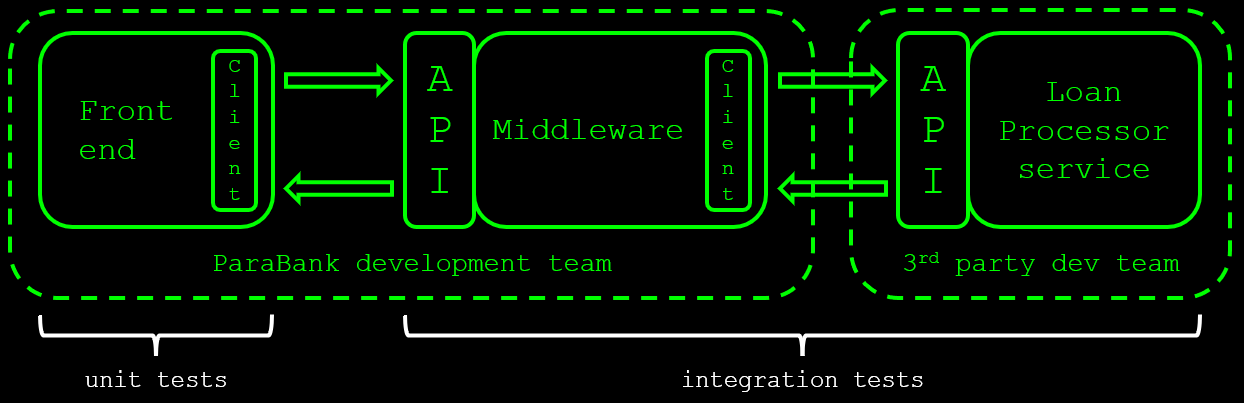

Step 2: Removing the third-party system from the equation

Another step in the right direction I’ve seen a lot of teams take is to replace actual third-party systems with simulations (mocks or stubs). Personally, I would prefer testing against ‘the real thing’ where possible, and use mocks mainly to test:

- Earlier - when you want to test against features that are still under development in ‘the real thing’

- More - when you want to test behaviour that is very hard or maybe even impossible to trigger in ‘the real thing’ on demand

- More often - when you cannot set up or invoke ‘the real thing’ often enough to fit your testing demands

In this case, because the loan processor is a third-party system, let’s assume it makes sense for the ParaBank development team to replace the loan processor with a mock, if only, for example, to test regularly how the ParaBank application holds up in case the loan processor is experiencing delays or returns errors or unexpected messages. There are more valid reasons or use cases for using mocks instead of real systems or components, but those are outside the scope of this blog post.

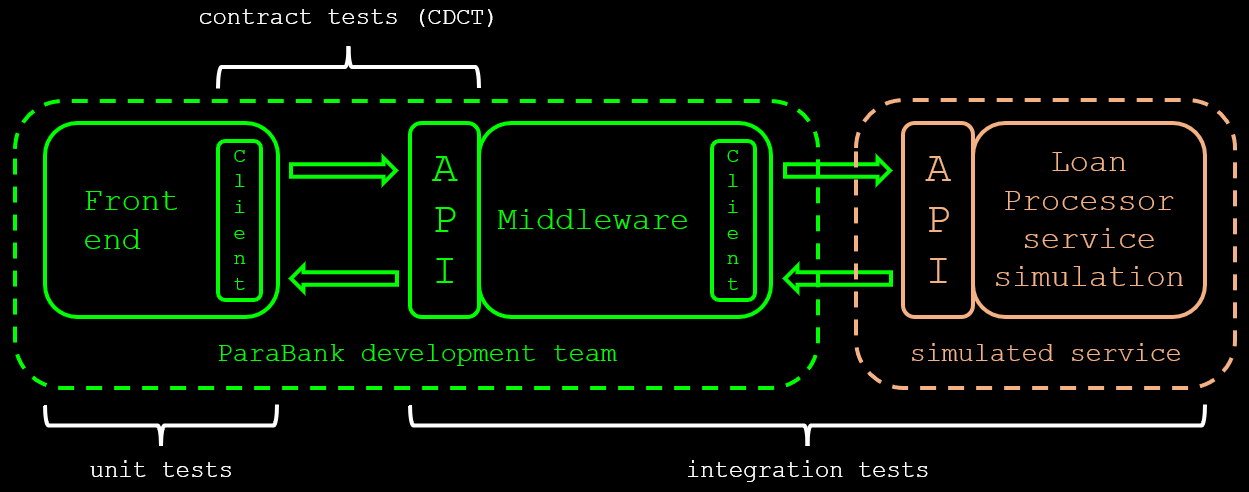

Replacing the actual loan processor with a simulation results in the following scope for our tests:

We have again successfully reduced the scope of our tests, but unfortunately, by addressing one problem we’ve introduced another: in this way, we’re not testing the actual integration between our ParaBank system and the third-party loan processor service anymore. That’s two for two when it comes to breaking down the integration testing puzzle and losing coverage around integrations between different components. Time to address that issue.

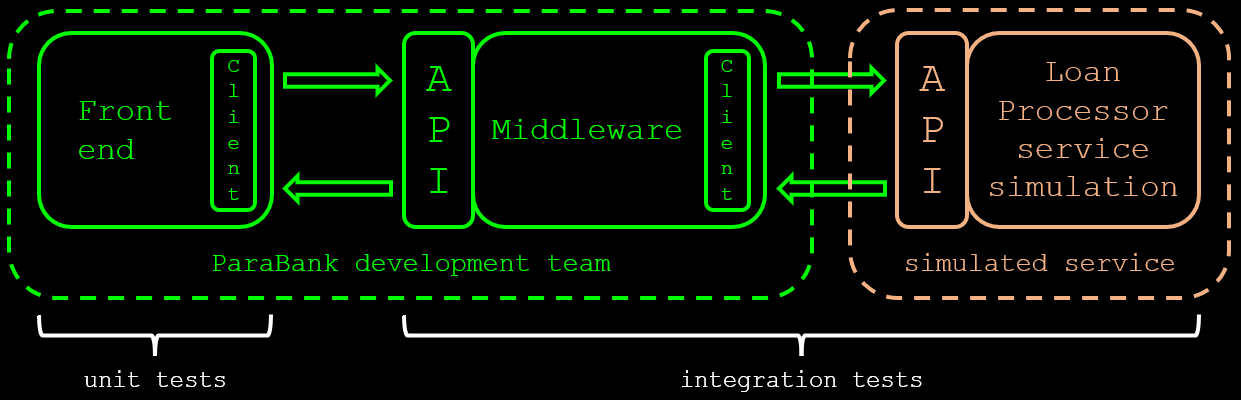

Step 3: Testing the integration between the frontend and the ParaBank backend

We can use contract testing as a way to help us test the integration between the ParaBank frontend and its backend. One of the biggest advantages of contract testing over other types of integration testing is that contract-based testing is asynchronous, meaning that while both consumer and provider have their duties in contract testing, they are not required to be deployed into a shared testing environment to exchange messages.

This helps perform our integration testing earlier in the development process, i.e., we can perform integration testing as early as when we’re working on our software in our local development environment. To phrase that differently, contract-based testing brings integration testing forward to the unit testing stage of our development efforts.

The first question we should ask in this case is ‘what flavour of contract testing?’. Since we’re dealing with both a consumer and a provider that are internal to ParaBank, and we want to do rich and detailed testing on the integration between frontend and backend, consumer-driven contract testing (CDCT) is a reasonable choice.

Tools like Pact or Spring Cloud Contract can help us implement CDCT here. After implementing CDCT for our frontend-backend integration, our test scope looks like this:

Step 4: Testing the integration between the backend and the loan processor service

Next, let’s move on to the other integration that suffered when we started breaking down our original E2E test into smaller pieces. Your first thought might be to see if CDCT would work here, too, but there are some challenges that might make implementing that a little harder:

- The service is developed outside ParaBank, which makes communication and conversation between development teams harder to establish, and

- The service might well be a public API offered to dozens of other online banking systems, too, which makes it much less likely for CDCT to be adopted by the loan processor development team

In this case, bidirectional contract testing or BDCT might be a more suitable option. With BDCT, both the consumer and the provider generate their own contract, and these are compared by an independent third party.

In the case of the Pact ecosystem, this will be Pactflow. BDCT lightens the burden on the provider side, as all they need to do, really, is to provide their OpenAPI spec, which makes it much easier to implement for this specific integration.

As an added bonus, there’s a good chance we can also reduce the number of situations that we simulated in step 2. The ‘happy path’ scenarios where the loan processor responds in the expected way should be covered by the contract now, leaving us to mock only those situations where the loan processor might behave in ways that aren’t described in the provider contract. Examples of these are delayed delivery of responses and server-side error responses (HTTP 5xx).

So, what have we done?

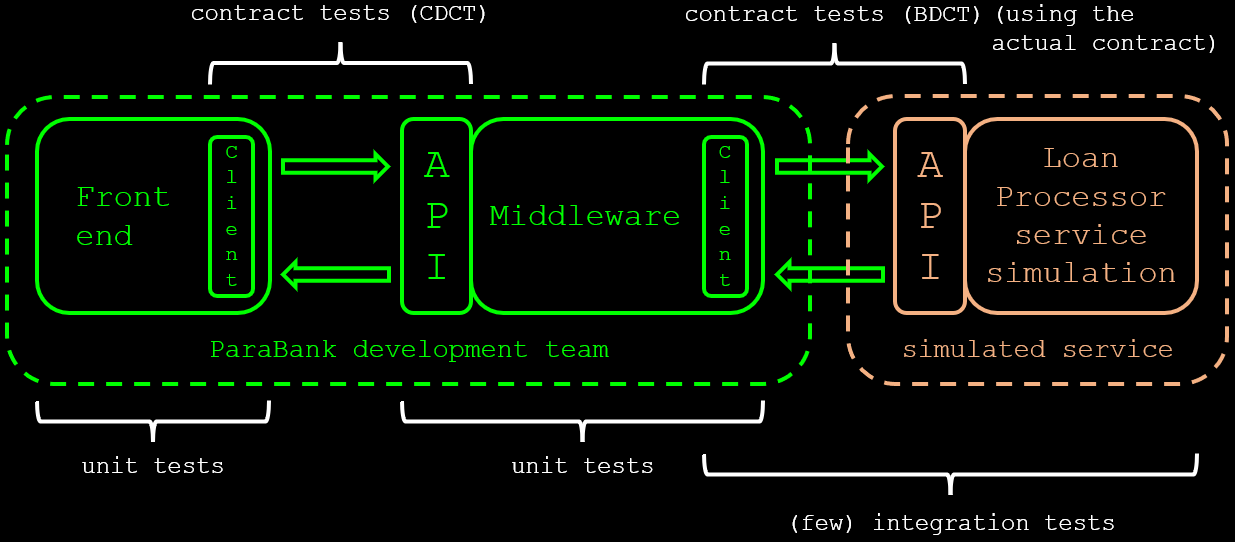

When we add the tests that verify the implementation of the backend again, our final testing breakdown for the loan application feature now looks like this:

We no longer have to rely on slow and expensive E2E tests that cross team, department and even company boundaries. We also no longer concern ourselves too much with (implicitly) testing the implementation of the third party loan processor service, as that was never our responsibility in the first place.

Instead, we have a comprehensive set of tests that cover the implementation of individual components in our system, combined with contract-based tests for detection of potential integration issues in current and future releases of individual components.

These tests will generally run much faster, and can be written and run much earlier in the development process, leading to faster feedback on the behaviour of our software.

Any questions or comments? I highly value your input.

"