Approaches to contract testing

Recently, I have started working on a new consulting project with a client in the UK. In this role, I am helping them implement contract testing to get better insights into the effects that changes introduced by individual teams on individual services have up- and downstream in a distributed software environment.

Now, most people, when thinking of or talking about contract testing, immediately think of the consumer-driven variant, often referred to as CDCT. However, contract testing is broader than ‘just’ CDCT. One of the first questions that we typically need to answer, and one that is often forgotten, is

What kind of contract testing approach would be the best fit for our situation?

In this blog post, I’ll present three different approaches to contract testing as well as their respective benefits and drawbacks. I am not going to discuss the merits of contract testing in general in this post. If you’re interested in reading more about that, I recommend you have a look at this blog post series instead.

Consumer-driven contract testing (CDCT)

As the name suggests, in CDCT it’s the consumer that is calling the shots, so to say. The consumer writes down their expectations about the behaviour of a provider in a contract, then passes that contract to the provider. IT is then the provider’s responsibility to demonstrate that they are able to meet all of the expectations expressed by the consumer.

It’s important to keep in mind here that a provider often has to demonstrate that they can meet the expectations of many, many different consumers. Each of these consumers hands over a contract with their specific expectations, and the provider has to meet all of them. This does mean that there can be conflicts of interest.

As a simple example, consider the situation where consumer A expects a provider to return a house number in an address as a string, whereas consumer B might expect the same provider to return that same house number as an integer. This is exactly the kind of potential integration issue that consumer-driven contract testing can uncover, and the kind of issue that often slips by unnoticed with more traditional approaches to integration testing. Or when no integration testing is done at all..

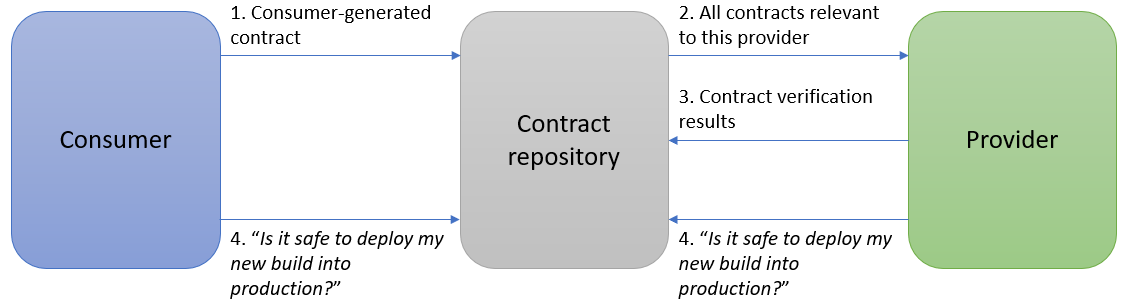

Here’s what the typical CDCT flow looks like:

In words:

- The consumer writes down their expectations about provider behaviour in a contract and publishes that to a central repository

- The provider pulls the relevant contracts from the repository and verifies whether it can fulfill all of the expectations in all of the contracts

- The provider publishes the verifications results back to the repository

- Both consumer and provider can query the repository for the latest verification results to see if there are any potential integrations issues, and if it is safe to deploy their next build into production

CDCT is particularly useful in situations where:

- consumers and providers are able to communicate easily to discuss testing situations and work out potential integration issues

- consumers are willing to spend the effort writing the expectations (pacts) and the tests that are required to generate the contracts from these expectations

More situations where CDCT works well, as described by the team behind Pact, one of the leading contract testing tools available today, can be found here.

CDCT does not particularly work well in situations where:

- the provider is a public API, i.e., it is hard or even impossible to maintain communication with the provider development team for individual consumer development teams

- the provider is not keen to do contract testing in general, or to listen and adapt to the needs of individual consumers (again, public APIs are a good example here)

More situations where CDCT does not work well are listed here.

Provider-driven contract testing (PDCT)

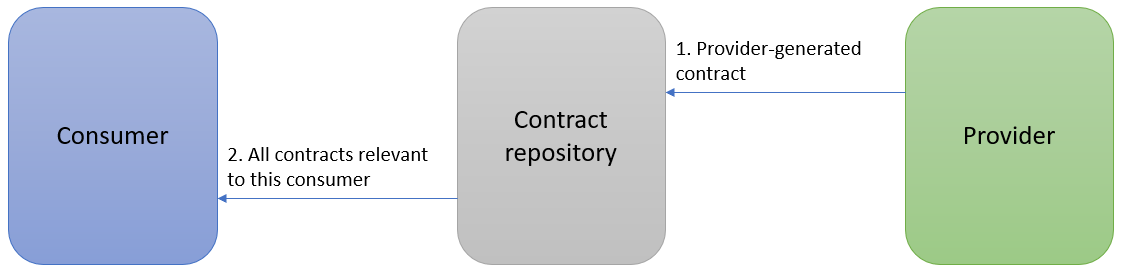

With PDCT, as you might have guessed from the name, it is the provider, not the consumer, who is ‘in charge’. Basically, it comes down to the provider issuing a contract expressing the way they behave and telling their consumers ‘this is what I do, deal with it’. A typical PDCT flow is therefore much more straightforward than the CDCT flow we saw earlier:

In words:

- The provider issues a contract expressing their behaviour

- Consumers use the contracts issued by the providers to determine whether they can communicate with the provider

In my opinion, the biggest drawback of PDCT is the lack of a feedback loop, i.e., there’s no way for the consumer to tell the provider ‘this is what works, this is what doesn’t’. The initiative and the power is fully in the hands of the provider, without any way for the consumer to voice their opinions or concerns, be it about provider behaviour or even provider design.

So, PDCT has the drawback of not having a feedback loop, while CDCT’s biggest drawback is probably the effort it takes to do it, do it well and keep doing it. This is the reason that recently, a third type of contract testing has emerged.

Bidirectional contract testing (BDCT)

With BDCT, neither the consumer nor the provider is significantly ‘in the lead’. Instead, with BDCT, both consumer and provider create their own version of a contract for a specific integration, the consumer contract containing (as in CDCT) their expectations about provider behaviour, the provider contract (as in PDCT) containing a specification of their behaviour.

The main difference between BDCT and the two other flavours of contract testing we discussed earlier is that with BDCT, contract comparison and verification is done by an independent entity instead of either by the consumer or the provider. Both parties upload their contract to this third party, which then compares the two and checks for potential integration issues.

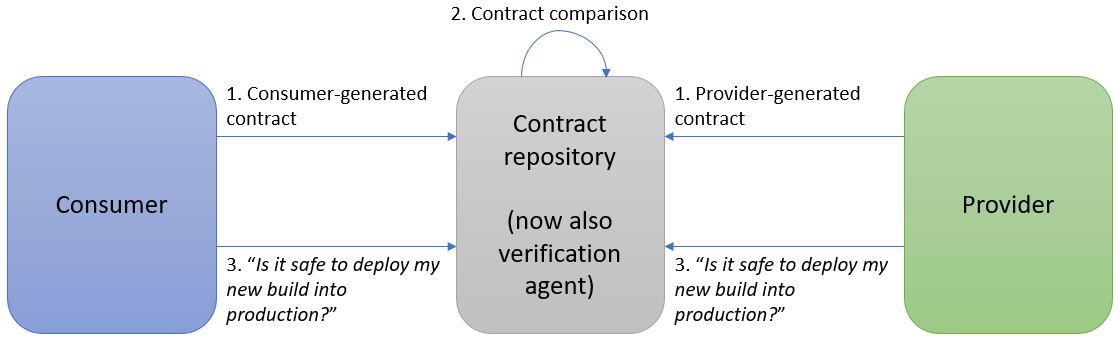

Here’s what that flow looks like:

In words:

- Both consumer and provider upload their contract to the contract repository

- The repository (which now also acts as a verification agent) compares the contract and checks for potential integration issues

- Both consumer and provider can query the repository for the latest verification results to see if there are any potential integrations issues, and if it is safe to deploy their next build into production

Currently, the only way I know of to do BDCT is by using Pactflow. If you want to see a working example of BDCT, here’s one I created and wrote about recently.

The biggest benefit of practicing BDCT is that the way BDCT is implemented within Pactflow and the wider Pact ecosystem means you can leverage existing technology to generate contracts more quickly, without having to depend on a full-blown Pact implementation.

A drawback for some teams and companies might be that right now, you need to use Pactflow (either the cloud version or an on-premise installation) to be able to practice BDCT.

As you can see, there’s more than one way to do contract testing, and each approach has their own benefits and drawbacks. Before you start throwing tools at your integration testing problem, it’s therefore a good idea to take a step back and first ask yourself ‘what is the best approach to contract testing for our particular context?’.

"