The four pillars of object-oriented programming - part 3 - polymorphism

This post was published on August 10, 2022In this blog post series, I’ll dive deeper into the four pillars (fundamental principles) of object-oriented programming:

- Encapsulation

- Inheritance

- Polymorphism (this post)

- Abstraction

Why? Because I think they are essential knowledge not just for developers, but definitely also for testers working with, reading or writing code. Understanding these principles helps you better understand application code, make recommendations on how to improve the structure of that code and, of course, write better automation code, too.

The examples I give will be mostly written in Java, but throughout these blog posts, I’ll mention how to implement these concepts, where possible, in C# and Python, too.

What is polymorphism?

Polymorphism is the ability of an object in object-oriented programming to take on different shapes. Originating from Greek, the term polymorphism literally translates to ‘many forms’.

Polymorphism allows programmers to attach more than one implementation to the same object or part of an object, as well as to access entities of different types through a single interface.

Polymorphism: an example

To get a better understanding of what polymorphism looks like, it’s first of all good to know that within object-oriented programming, two types of polymorphism frequently occur: overriding and overloading. You could say that even polymorphism itself has multiple shapes. How meta…

Overriding in action

Let’s take a look at overriding first. In the previous blog post, we defined a class SavingsAccount that inherited properties and methods from its parent class Account.

Furthermore, in the first blog post, we implemented the withdraw method in the Account class, which contains some general business logic (preventing us from depositing a negative amount), but also some business logic that is specific to a savings account (preventing overdrawing from a savings account).

We can argue that this second piece of logic should be part of the SavingsAccount class, instead of in the Account class, as it is specific to savings accounts. As a result, both classes should have their own implementation of the withdraw() method.

And that’s exactly what overriding enables you to do: override the definition of a method from a parent class (here: Account) in a child class (here: SavingsAccount).

So, this means we can now have an implementation for withdraw() in the Account class that looks like this:

public void withdraw(double amount) throws WithdrawException {

if (amount < 0) {

throw new WithdrawException("You cannot withdraw a negative amount!");

}

this.balance -= amount;

}and another definition for withdraw() in the SavingsAccount class that overrides the one in Account:

@Override

public void withdraw(double amount) throws WithdrawException {

if (amount < 0) {

throw new WithdrawException("You cannot withdraw a negative amount!");

}

if (amount > this.balance) {

throw new WithdrawException("You cannot overdraw on a savings account!");

}

this.balance -= amount;

}Please note that while using the @Override annotation is not strictly necessary in Java, i.e., leaving it out doesn’t generate any compiler errors, using it is recommended to make your code explicitly show that a parent class method implementation is being overwritten.

So, by applying polymorphism by means of overriding, we now have a situation where we can do both this:

Account account = new Account(AccountType.CHECKING);

account.deposit(20);

account.withdraw(30); // this does not generate an exception as overdrawing on a checking account is allowedas well as this:

SavingsAccount account = new SavingsAccount();

account.deposit(20);

account.withdraw(30); // this generates an exception as overdrawing on a savings account is not allowedAnother note: we do still have some room for improvement here. The fact that a checking account is created through the Account type, while a savings account has its own data type is noy very elegant. We’ll address this in the fourth and final blog post in this series, when we start talking about abstraction.

Overloading in action

The other type of polymorphism I would like to cover in this blog post is overloading. Overloading, in object-oriented programming, is the ability to define multiple methods with the same name, but with different sets of arguments.

As an example, let’s define a second constructor (a constructor is a special kind of method) for the SavingsAccount class:

public class SavingsAccount extends Account {

private final double interestRate;

public SavingsAccount() {

super(AccountType.SAVINGS);

this.interestRate = 0.03;

}

public SavingsAccount(double interestRate) {

super(AccountType.SAVINGS);

this.interestRate = interestRate;

}This allows us to either create a savings account with a default interest rate of 3% using the first constructor, or create one with a custom interest rate using the second constructor.

You can define as many overloads for a constructor, or for any method in general, as you want, as long as either the data types of the arguments, the number of arguments, or both, are unique. Why? Because Java needs to know which version of your constructor or method it needs to invoke at runtime, and the way it does so is by looking at the number and the data type of the arguments passed to that constructor or method.

Polymorphism in other languages

In C#, overriding works much the same way as in Java. However, you need to allow a method to be overridden in a parent class explicitly by using the virtual keyword:

public class Employee

{

protected decimal _baseSalary;

public Employee(decimal baseSalary)

{

_baseSalary = baseSalary;

}

public virtual decimal GetSalary()

{

return _baseSalary;

}

}public class SalesEmployee : Employee

{

protected decimal _targetBonus;

public SalesEmployee(decimal baseSalary, decimal targetBonus) : base(baseSalary)

{

_targetBonus = targetBonus;

}

public override decimal GetSalary()

{

return _baseSalary + _targetBonus;

}

}Python, too, supports method overriding, in a really straightforward manner:

class Employee:

def __init__(self, base_salary):

self.base_salary = base_salary

def get_salary(self):

return self.base_salaryclass SalesEmployee(Employee):

def __init__(self, base_salary, target_bonus):

Employee.__init__(self, base_salary)

self.target_bonus = target_bonus

def get_salary(self):

return self.base_salary + self.target_bonusMethod overloading in both C# and Python is even easier than in Java, since both languages support optional method arguments as well as default argument values. For example, the two constructors we’ve seen for the Account class in Java can be recreated in a single constructor in both C# and Python by using a default value for an argument:

public class SavingsAccount : Account

{

protected double _interestRate;

public SavingsAccount(double interestRate = 0.03) : base(AccountType.SAVINGS)

{

_interestRate = interestRate;

}class SavingsAccount(Account):

def __init__(self, interest_rate = 0.03):

self.interest_rate = interest_rateIn both cases, you’re now able to either create a SavingsAccount with the default interest rate of 3%, or create one with a custom interest rate value.

Polymorphism in automation

While I myself do not apply polymorphism very often in my automation solutions, there are some cases where it can be useful, especially when we’re looking at overloading methods. For example, when I have a Selenium helper method that I want to be able to either use a default timeout length, or pass in a custom (often a longer) timeout value in specific cases.

Here’s what these helper methods may look like, for example in case of waiting for a button to become clickable before attempting to actually click it:

protected void click(By locator) {

click(locator, 10);

}

protected void click(By locator, int timeoutInSeconds) {

try {

new WebDriverWait(this.driver, Duration.ofSeconds(timeoutInSeconds)).until(ExpectedConditions.elementToBeClickable(locator));

driver.findElement(locator).click();

}

catch (TimeoutException te) {

Assertions.fail(String.format("Exception in click() (timeout was %d seconds): %s", timeoutInSeconds, te.getMessage()));

}

}In this way, you can either call click(By.Id("someElement")) in your scripts, using the default timeout value of 10 seconds, or specify for example a 20 seconds timeout for specific cases by calling `click(By.Id(“someSlowLoadingElement”), 20);

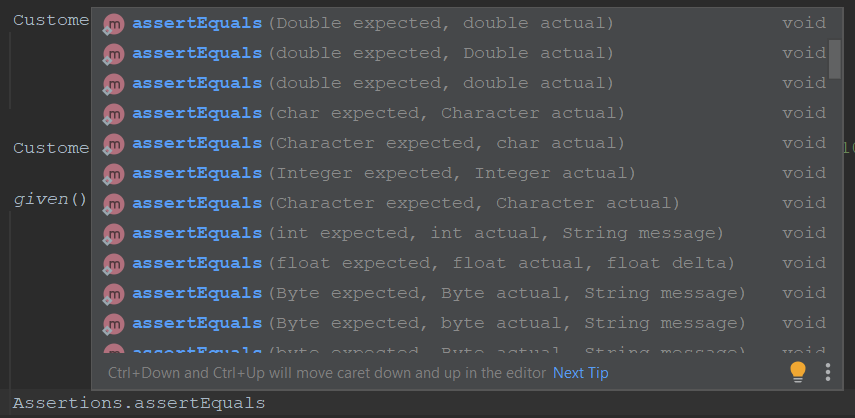

Another case where, even if you haven’t implemented it yourself, you benefit from the power of overloading is when choosing one of the many overloads of the assertEquals() method in JUnit (or TestNG):

I don’t use overriding as much in my automation code as I do overloading, but there are bound to be cases where you have found it to be useful. In that case, feel free to leave an example in the comments.

In the fourth and final blog post in this series, we’ll take a closer look at the last of the four fundamental principles of object-oriented programming: abstraction.

"